By Roberta Rincón, Ph.D., Manager of Research, SWE

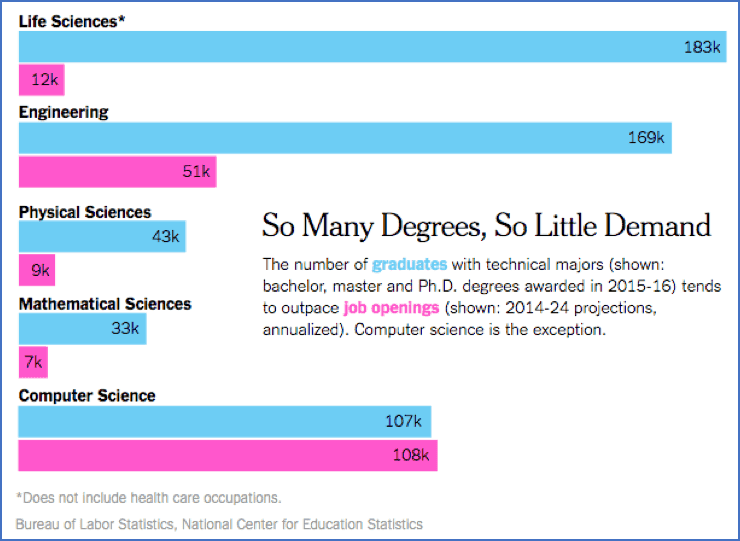

I was recently asked my thoughts about a New York Times article posted on November 1st, where the author made a compelling argument against the STEM shortage. He noted that our national focus on increasing STEM graduates ignores the fact that certain STEM disciplines are in higher demand than others, and shortages only exist in a handful of STEM fields. By generalizing the STEM shortage, we are misleading future graduates with promises of lucrative job prospects that don’t exist for most STEM graduates.

The piece of the argument that drew my attention was a graph that showed that we are graduating far more engineers than we need to meet demand (see below).

This graph made me pause and think. My first reaction was that it wasn’t true, that there must be something missing, something not being considered. But, after double-checking the sources, I had to concede that the graph was accurate. So, of course, this made me wonder: Are we actually experiencing a surplus of engineers, and are the efforts we are making to increase engineering graduates unnecessary?

After some research, I have concluded that our efforts to increase engineering graduates are in fact necessary because there continues to be a strong demand for STEM graduates, and engineering graduates in particular. Granted, it does vary by discipline and geographic region. But unemployment rates for STEM graduates (3.8%) are lower than those of non-STEM graduates (4.3%), and far lower than the U.S labor force unemployment rate (8.1%). Salaries also continue to outpace those of non-STEM graduates, with median salaries for STEM graduates in 2013 at $65,000 compared to $52,000 for non-STEM graduates. The National Science Foundation notes that “the application of science and engineering knowledge and skills is widespread across the technologically sophisticated U.S. economy and not limited to jobs classified as science and engineering,” which indicates that STEM graduates are versatile and can apply their knowledge and skills to a variety of STEM and non-STEM occupations.

This has resulted in competition for STEM graduates that extends far beyond traditional STEM jobs, leaving STEM companies struggling to fill their science and engineering positions.

So why the controversy over the existence of a STEM shortage? Much of this is due to how the federal government defines a STEM occupation. Clearly, if an engineering graduate is working as an engineer, then she is categorized as a STEM worker. But what if she is teaching in an engineering college? Or if she is an engineering manager? Or she uses her engineering knowledge in sales? The Bureau of Labor Statistics and the U.S. Census Bureau do not categorize her as a STEM worker in such cases.

These narrow definitions impact our ability to understand retention in the engineering profession because we consider such workers as having left the profession – not exactly accurate, but it all depends on how our data sources define STEM. For example, the U.S. Census Bureau reports that only 33% of engineering graduates between the ages of 25-64 were working in engineering occupations in 2012, while the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation reported in 2013 that 77.4% of engineering and engineering technology graduates were working in a job related to their major. This same report found that 73.2% of computer and information science (CIS) graduates were employed in a job related to their major, and noted that both CIS and engineering graduates had lower unemployment rates than the general college graduate population as a whole.

STEM continues to be in high demand. The U.S. Department of Commerce provided an update in March 2017 that noted that STEM employment is growing at a much faster rate than non-STEM employment, and STEM job growth is expected to continue to outpace non-STEM growth through 2024. STEM workers continue to command higher wages than their non-STEM counterparts – and the increasing wage differential supports the argument of the existence of a shortage of STEM talent. The update notes that, regardless of whether a STEM degree holder works in a STEM or non-STEM occupation, they can expect to earn more than non-STEM degree holders (all other factors constant).

The bottom line is that the answer to the question of whether a shortage exists is complicated. To quote the Bureau of Labor Statistics in an article published May 2015: “STEM crisis or STEM surplus? Yes and yes.” It’s a question that cannot be answered without caveats.

As we strive to increase recruitment and retention in engineering, our work to diversify the engineering profession is critically needed to meet the demand for STEM talent. We must continue to encourage underrepresented groups to complete engineering degrees and enter the engineering profession. Knowing that the demand for skilled STEM workers is growing only adds to the urgency of our work.

Author

-

![Is There a Shortage of STEM Jobs to STEM Graduates? It’s Complicated. [] SWE Blog](https://alltogether.swe.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/swe-favicon.png)

SWE Blog provides up-to-date information and news about the Society and how our members are making a difference every day. You’ll find stories about SWE members, engineering, technology, and other STEM-related topics.

I have to wonder why they list Computer Science separate from Engineering. Software engineering is … engineering.