By Erik LacitisSeattle Times staff reporter

Originally published June 6, 2016 in the Seattle Times.

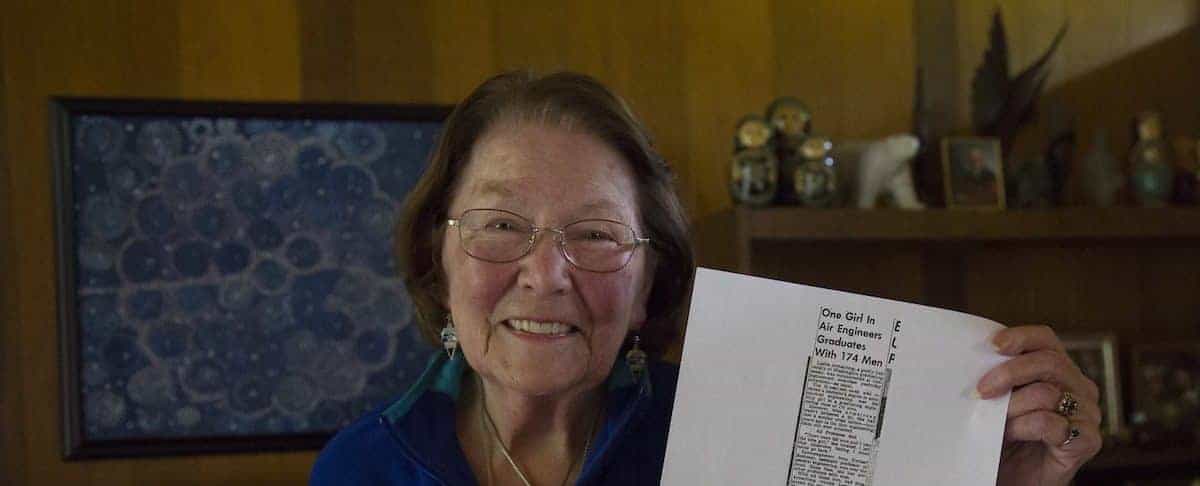

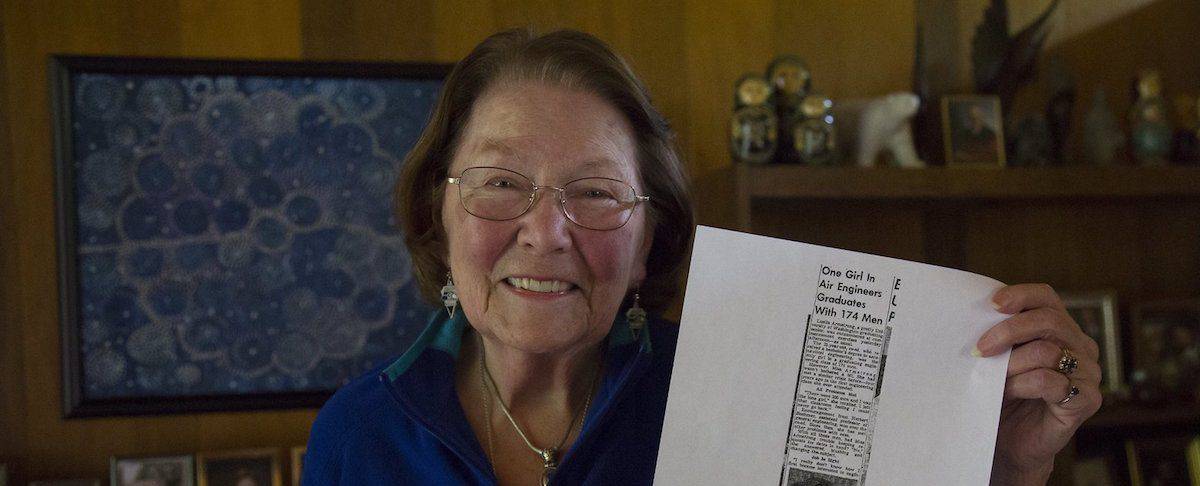

In 1951, Luella Armstrong, now 86, was a graduate from what is now the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics. The story was headlined, “One girl … ” Times have changed and a few corrections are in order.

It’s a bit late — 65 years late — but we’re happy to clarify a story this paper ran on Sunday, June 10, 1951.

For all those years the story has gnawed at Luella Armstrong, now 86. It concerned that year’s graduation coverage at the University of Washington. Back in those days, stories like that began on Page 1 and continued to big spreads inside that included the name of every graduating senior. There was a special story about Armstrong inside. The headline was, “One girl in air engineers graduates with 174 men.”

You can pretty well guess what’s gnawed at Armstrong for more than six decades during her accomplished career in aeronautical engineering with Boeing. In one paragraph, the story asked Armstrong if her fellow students hit on her: With all those men, had Miss Armstrong trouble keeping requests for dates in hand? it said. “No,” she answered, blushing and changing the subject.

Uhhh.

That same story today would have exploded with the internet commentarial. Those were different times.

In that story, Armstrong herself says, “ … I was the lone girl … ” But if you are being interviewed and that term is used, and those are the times, that’s how you answer, she says.

Armstrong reflects on her time at the University of Washington and what it was like being the only woman in her engineering classes. Armstrong went on to a lengthy career as a Boeing engineer.

Armstrong, of Lake Forest Park — personal computer in room, laptop in the living room — can tell you about those times. She remembers taking a class that involved working at the foundry shop and producing castings. She wore jeans there. After she was done at the shop, she switched to a skirt.

“No woman was seen on campus in jeans or pants,” says Armstrong.

She remembers one professor, upon first seeing a woman in his class, telling her, “You can stay, but I’ll barely pass you.”

“I said, ‘OK,’ ’’ says Armstrong. After that the prof ignored her and did give her that passing grade.

Still, she remembers most professors treated her “with respect and encouragement,” she says, and “outnumbered those who didn’t want me in their classes.”

The battles continue

Armstrong was among the trailblazers for today’s young women — who still are in the minority in most science fields, and in many cases still fighting for acceptance.

According to the National Science Foundation, in 1975, women earned only 2 percent of bachelor’s degrees in engineering. Four decades later, in 2014, that had improved to 20 percent.

Luella Armstrong holds a 1951 Seattle Times article with the headline “One girl in air engineers graduates with 174 men.” Armstrong, 86, had a distinguished career in aeronautical engineering at Boeing and now lives in Lake Forest Park. (Sy Bean/The Seattle Times)

Which means women engineers are still very much in the minority and fighting their own current battles. In 2015, Isis Wenger, a software engineer, appeared in a recruitment ad for her company, OneLogIn of San Francisco. She was attacked online as basically being too good-looking and not “remotely plausible” for what “a female software engineer looks like.” That started other female engineers posting their photos with the hashtag #ILookLikeAnEngineer.

Colleen Layman, of Janesville, Wis., president of the Society of Women Engineers, says the Dilbert cartoon of an engineer still is how many imagine the profession — “a guy with a pocket protector.”

Attitudes will start changing, she says, when this image of a woman engineer is more the norm: “vibrant, attractive, outgoing.”

Layman says girls start losing interest early in science classes because the classes are geared for boys.

With Legos, for example, she says, “Boys want to build something and then knock it down.”

Girls, she says, “want to build something that to their minds benefits society, a home for pets or something. It’s the different ways a male mind thinks and a female mind thinks.”

“I was very fortunate”

Armstrong was an exception then and now. She was the daughter of a diesel mechanic dad and a stay-at-home mom. She graduated in 1947 from Overlake High School (now Bellevue High), with a 3.98 GPA. She was class valedictorian.

She got all A’s, except for a B in a cooking class. “I just wasn’t that interested in it.”

Back then, if you were a studious high-school girl, you were supposed to go into teaching or nursing, says Armstrong. She was distinctly uninterested in those careers. What she liked was math and science.

“I had a wonderful, wonderful math teacher. His name was Frank Odle. He said, ‘Why don’t you think about engineering?’ It was quite something in 1947 for a teacher to suggest that,” says Armstrong.

She wasn’t the first woman to attend the engineering school, but certainly among the first.

After her first day of classes, she was rattled and told her family, “I’m not going back.” Her mother said, “Oh, yes, you will.”

As for having to fend off the male students, it turned out most were much older. They were returning servicemen on the GI Bill.

“Some had families. I was very fortunate. They treated me like I was a sister,” she says.

Armstrong loved her classes. Math? You bet! Working with a slide rule? Yes!

Six months before graduating, she was part of a UW team contracted to do wind-tunnel testing.

She went right onto a full-time job at Boeing’s Plant 2 on East Marginal Way South.

She worked on projects that engineers would readily understand, but not the rest of us. Structural dynamics. Airplane landing loads. Flutter analysis.

Then she met Bill Mudge at a party. He worked in direction and production for a local TV station. They married in 1955 and Armstrong became pregnant the next year.

In those times, she says, if you were a woman working at Boeing and got pregnant, “You had to leave in the first month or two.”

“I just ignored it,” she says, “and continued to work until it was obvious.”

The couple would have two sons and a daughter. Armstrong stayed at home because that’s what moms of her generation did.

The couple divorced in 1976.

“I kind of lost myself in that marriage,” says Armstrong. “I put everybody else first.”

It was time to get back to work. But Boeing wasn’t hiring then. Armstrong found a job setting up billing for a home-nursing company.

Then, at a party, she mentioned to a woman there that her background was as an aeronautical engineer. The woman happened to be the executive secretary for the head of Boeing’s CAD/CAM (computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing) division.

He called her. She was hired.

“Through the years I’ve had a lot of guardian angels,” Armstrong says.

Back to her favorite work

It wasn’t easy in 1979 rejoining the world of engineering and its new computer stuff.

“Just calm down, you can do it,” the young engineers would tell their 49-year-old colleague.

And she did.

Armstrong has displayed in her home a “Certificate of Outstanding Performance” given to her by Boeing for her leadership in the 747/767 airplane programs.

At times she was a sort of bridge between old-school and new-school engineering.

“I was very patient with young engineers. Everything they do is on a computer. They had no concept of 3D. I would explain to them that you have to visualize,” says Armstrong.

One time, she remembers, a problem with a design was because one of the young engineers had put the vector in the wrong direction. Armstrong didn’t want to retire in 1995, but she says Boeing was offering an incredible package. She took it.

It wasn’t Armstrong who contacted this paper about that 1951 story. It was one of her grandsons, Ryan Anderson, 21.

“She’s my biggest hero,” he says. Anderson is graduating from Central Washington University with a degree in musical theater.

He always has loved singing, he says. When he was in first grade, it was Armstrong who drove him to audition for the Northwest Boychoir. From the time he was 6 until he was 16, his grandmother took him twice a week to practice with the choir.

Through the years, Anderson remembers his grandma mentioning that newspaper article and the “girl” reference. He asked The Seattle Times that the record be set straight about that story from 65 years ago.

So here it is.

As Luella Armstrong says about being an aeronautics-engineering grad, “I was a woman. I wasn’t a girl.”

Erik Lacitis: 206-464-2237 or elacitis@seattletimes.com Twitter @ErikLacitis”

Author

-

![Seattle Times Corrects a 1951 Story about an Engineering Grad [] SWE Blog](https://alltogether.swe.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/swe-favicon.png)

SWE Blog provides up-to-date information and news about the Society and how our members are making a difference every day. You’ll find stories about SWE members, engineering, technology, and other STEM-related topics.