As even seemingly savvy companies have learned the hard way, diversity training can backfire, leading employees to feel angry, resentful, and betrayed. A less-dramatic, but equally frustrating unintended outcome: Diversity training sessions are often seen as ineffective.

Researchers are just beginning to unravel the science behind successful diversity training — and, in the process, gaining respect for the rigorous analysis they have brought to the way such training should be conducted. “[Diversity training] is not just something that should be done because it’s the right thing to do,” said Katerina Bezrukova, Ph.D., associate professor of organization and human resources at the University of Buffalo’s School of Management and one of four co-authors of a seminal analysis assessing the effects of diversity training. “If you don’t do it right, you can get a lot of horrible and tragic outcomes.”

The researchers’ analysis examined more than 40 years of studies, fusing data from 260 studies and more than 29,000 participants from a variety of fields. The 260 independent samples assessed the effects of diversity training on four training outcomes over time and across characteristics of training context, design, and participants, according to the report, titled “A Meta-Analytical Integration of Over 40 Years of Research on Diversity Training Evaluation” (Bezrukova, Spell, Perry, and Jehn, 2016).

The analysis used models from diversity training literature and psychological theory to generate theory-driven predictions.

DEFINING A FRAMEWORK

Due to the complexity of the topic and the strong emotional responses it can bring, diversity training is a branch of its own in the study of training methods. Dr. Bezrukova notes that the research team conducted its analysis within the established framework of diversity training and philosophy. Citing earlier work, the authors write, “We define diversity training as a distinct set of instructional programs aimed at facilitating positive intergroup interactions, reducing prejudice and discrimination, and enhancing the skills, knowledge, and motivation of participants to interact with diverse others (Pendry et al., 2007).”

The study found training is most effective when it is delivered over an extended period, integrated with other initiatives, and designed to increase both awareness and skills. The setting, whether it consisted of young people on college campuses or corporate employees of varying ages at their job sites, made no difference. Based on a review of the overall research, neither voluntary nor mandatory training was clearly superior, though some researchers assert that mandatory training frequently backfires.

Among the positive indicators: People can learn about other cultures by working with those of different and diverse backgrounds. The long-term aim of effective diversity training could be what diversity trainers Thomas Kochman, Ph.D., and Jean Mavrelis, co-authors of Corporate Tribalism: White Men/White Women and Cultural Diversity at Work, call cultural pluralism, or an environment in which people appreciate and value one another’s norms, behaviors, and attitudes.

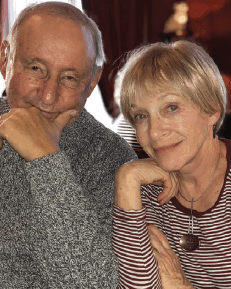

Dr. Kochman and Mavrelis, a husband-and-wife team whose firm, Kochman Mavrelis Associates, is based in the Chicago suburb of Oak Park, lead diversity training sessions in which employees’ differences are openly discussed. “Ours is not an assimilationist model,” Mavrelis said. “It’s where there is no ‘one way.’ … If we take things that aren’t in the rulebook and make them explicit, we could say, ‘A lot of people [who work together] could be great leaders.’ We make the implicit explicit.”

“Building trust is the key,” Dr. Kochman said. “With cultural pluralism, there’s a greater social equity. People want to be respected for their differences. That sets a dynamic into motion where, if you want to be treated as you see yourself, others have to know how you see yourself. That’s where the learning comes in, the educational aspect. In our training, we don’t make it accusatory. We make it educational, and minimize the defensiveness.”

“Diversity can be unbelievably painful when you can’t understand [a new culture], but [at the same time], you want new experiences and [the] sheer knowledge that comes from a different perspective or [a different] take on a problem,” Dr. Bezrukova said. Diversity training is equally complicated, since people can fall back into their old patterns of attitudes and behaviors, even while their cultural knowledge remains consistent or has even increased.

“Cognitive learning tends to increase over time,” said Dr. Bezrukova, who grew up in Crimea and became interested in diversity when she attended The Wharton School at the University of Pennsylvania as a postdoctoral researcher and social psychologist. Coming from a decidedly different culture, she has had little in common with everyone she has worked with.

“The attitudes this [diversity] training attempts to change are generally strong, emotion driven, and tied to our personal identities, and we found little evidence that long-term effects to them are sustainable,” Dr. Bezrukova said. “However, when people are reminded by their colleagues or even by the media of scenarios covered in training, they are able to retain or expand on the information they’ve learned,” she said.

It’s the kind of learning that needs constant reinforcement. “It’s critical to offer diversity programs as part of a series of related efforts, such as mentoring or networking groups for minority professionals,” Dr. Bezrukova said. “When organizations demonstrate a commitment to diversity, employees are more motivated to learn about and understand these societal issues and to apply that in their daily interactions.

“If there is good support — through hiring practices, promotions, and clear goals — anything in support of diversity, the coordinated efforts help,” she said. People who become more attuned to diverse cultures tend to seek out information verifying their new insights on TV and social media, for example. “I was happy to see people [involved in the studies] increase their cognitive knowledge,” Dr. Bezrukova said. “Just knowing about something provides better understanding and leads to better relationships with people who are different. That’s a positive trend.”

For diversity training to have staying power, a simple lecture won’t cut it, the research found. Diversity training participants responded more favorably to programs that used several instruction methods, including lectures, discussions, and exercises. “If it’s just a one-click response setup, it’s not going to work that well,” Dr. Bezrukova said.

Dr. Bezrukova’s co-authors on the study are Karen Jehn, Ph.D., professor of management, The University of Melbourne Business School; Jamie Perry, Ph.D., assistant professor, Cornell University School of Hotel Administration; and Chester Spell, Ph.D., professor of management, Rutgers University School of Business-Camden.

THE DIFFICULTY OF CHANGE

Interestingly, another meta-analysis on diversity training outcomes was conducted several years prior to Dr. Bezrukova’s. That study examined quantitative evidence that diversity training changes affective-based, cognitive-based, and skillbased trainee outcomes (Kalinoski, et al., 2013). Consistent with Dr. Bezrukova’s study, this earlier work, “A Meta-analytic Evaluation of Diversity Training Outcomes,” also found that longer trainings were more effective than shorter trainings.

Additional findings from the Kalinoski study include that trainings with active (e.g., exercises) rather than passive (e.g., lecture, video) forms of instruction and implementing face-to-face rather than computer-based formats were more effective in changing attitudes of participants. They also looked at trainee motivation, noting that training is more effective for those who perceive that the training is important and relevant.

Significantly, the authors note the need for more research examining diversity-training effects that account for trainees’ attitudes prior to training. They state that one would expect little change in attitude from trainees who go in with a favorable attitude toward diversity.

Seeking insight and possible solutions, some scholars have examined the effectiveness of awareness-based and behavioral approaches to diversity training. Margo Monteith, Ph.D., professor of psychological sciences at Purdue University, West Lafayette, Indiana, said, “Stereotypes are so ingrained in our culture, they become a habitual way of responding. The role of motivated self-regulation really is about breaking a bad habit.”

Practicing self-regulation requires effort and practice, she said. “It requires continual efforts and vigilance toward understanding the nature of one’s biases and working on regulating them. It’s across time where people become better at generating alternative types of responses (other than the stereotypical knee-jerk responses).”

So, how do people see that they are biased? Confrontation can be an effective tool in diversity training, but, in dealing with sexism, confrontation must be paired with evidence that people participating in the training exhibit bias — and that the results have repercussions, said Dr. Monteith, who is co-editing a new book, Confronting Prejudice and Discrimination: The Science of Changing Minds and Behaviors, with Robyn Mallett, Ph.D., an associate professor of psychology at the Loyola University Chicago. That’s because, as Dr. Monteith described it, “Sexism is a unique kind of ’ism. Women and men have communal relationships. Women often are viewed very positively in terms of attitudes. In the president’s words, ‘I have respect for women,’” she said.

Logically, it follows that diversity training should include hands-on activities. That might include showing participants identical resumes — one from a man and one from a woman. When the diversity trainee decides to “hire” the man, the response would be to present the evidence of the identical applications.

“Presenting that evidence has clear implications for the well-being of women versus men,” Dr. Monteith said. “People with (higher internal motivation) will then experience this negative self-directed affect and become more concerned about their biases.

“Encouraging reductions of sexist biases often requires that people have experiences where their own biases come to light,” Dr. Monteith said. For those who are less motivated to see their own biases, the appropriate motivation can spring from showing that they are violating society’s or their employer’s norms and values, rather than browbeating them or failing to offer them choices, she said. The idea is to create clear norms of behavior.

“Any time an authority figure models a certain behavior, people are more likely to go along with it,” Dr. Monteith said. “And grassroots movements, even the #MeToo movement, people coming together who aren’t in positions of power but gathering in solidarity and presenting their common experiences, can have a positive effect.”

CHALLENGES FOR INDUSTRY AND ACADEMIA

As the workforce becomes more diverse, researchers studying all sorts of companies and industries are identifying the “sore points” — or places where a lack of understanding and/or bias causes problems to become evident. “Our research shows that for any given situation, the type of program and the way it’s designed, especially with respect to how the rest of the organization operates, are very important,” Dr. Bezrukova said.

For example, Dr. Spell, Dr. Bezrukova, and their colleagues Sayan Mukherjee, Ph.D., assistant professor at the T.A. Pai Management Institute, and Alok Baveja, Ph.D., professor at Rutgers University, are studying how diversity in police departments may be connected with bias in arrests and unequal treatment of minorities. Some high-profile cases of bias and wrongful shootings of innocent citizens were major social issues even before the 2014 Ferguson riots and others since then, energizing groups such as Black Lives Matter.

Another project, presented in 2017 at the Industry Studies Association conference in Washington, D.C., examined the role bias plays in the way patients are treated in hospitals, and how diversity of both medical staff and patients can result in differential treatment. The study found that patients in some demographic groups showed higher chances of being readmitted to the hospital for the same condition within days of discharge. Patients who were single, nonwhite, older, low income and who spoke English as a second language, and those with poor access to food, had a higher likelihood of being readmitted within seven days.

In yet another area of research, in separate studies Patrick McKay et al. (2011) and Eden King et al. (2011) have shown how the extent to which the proportion of minorities in the workforce is representative, or matches, that of the business customer base, matters in how customers are treated.

Offering additional perspective, Alexandra Kalev, Ph.D., professor of sociology at Tel Aviv University and co-author with Frank Dobbin, Ph.D., professor of sociology at Harvard University, of the Harvard Business Review article “Why Diversity Programs Fail” (Dobbin and Kalev, 2016), said diversity training should never be a requirement. “There is no in-and-out, quick solution for diversity,” Dr. Kalev said. “The actual experience of training often creates more antagonism than buy-in and motivation.

“Most training is mandatory. People have to sit in a room instead of doing what they are busy with and listen to how bad and biased they are,” she said, as this can be the case particularly when evidencebased confrontation methods are not handled with the necessary sensitivity and thoughtfulness. While diversity training has become “a huge industry, run by well-meaning people,” Dr. Kalev posits it can be done correctly at a much lower cost and in a much less flashy way than many companies implement it. “It’s not going to go away, so we need to make sure to do it right,” she said.

From Dr. Kalev’s perspective, doing it right would mean:

- Implementing diversity training on a voluntary basis — and only after employees understand the business case for diversity, and as part of a larger organizational project. “Diversity training should be held only when it’s relevant,” Dr. Kalev said, echoing the point that training needs to be part of a larger effort that includes examining and instituting new company policies and processes. “Sometimes it’s not even about biases. Sometimes women must attend meetings from 5 p.m. to 7 p.m., and if not, they’re left out. Yet they may have to pick up their children from school. In cases where we’re talking about arrangements that aren’t family friendly, move the meetings to no later than 3 p.m.” She emphasized that, “When managers understand the business case for their department, their company — that it’s not about replacing white men; just getting the best workers, it works,” she said. “When managers get to devise the plans — when they are engaged — this is when it works.”

- Using contact theory. Let employees from different backgrounds, roles, and ethnicities work together. For example, a cross-functional project team comprising employees from various departments, a mix of salaried and hourly workers from a research and development department, along with those who work in assembly, and from customer service, can weaken the participants’ biases by learning more about one another.

- Engaging mentors. “Once senior executives do one mentoring assignment, they start recruiting other managers and take it on as their own,” Dr. Kalev said. “This kind of engagement creates a buy-in. That’s one of the mechanisms we see works — creating buy-in of the idea that diversity is important, not threatening, and a goal that the leaders can help achieve.”

- Implementing targeted recruitment. Seek diverse job candidates and have line managers interview them. “It creates commitment, engagement, contact. We see the numbers add up.”

Dr. Kalev notes that the above approaches are “not as costly as training, and even small organizations can adopt them.”

FINAL THOUGHTS

The work of inclusiveness — making space for everyone and everyone’s culture, experience, and personality — is as difficult and complicated as people themselves. We all have biases, yet the search continues for the best way to open everyone, including the most resistant people, to change.

The effort will require that mentors, colleagues, executives, managers, and hourly workers take on one another’s struggles with a buy-in deep enough to help each other, honor each other, and hear each other out.

References

Bezrukova, K., C.S. Spell, J.L. Perry, and K.A. Jehn (2016). “A Meta-analytical Integration of Over 40 Years of Research on Diversity Training Evaluation.” Psychological Bulletin 142(11): 1227-1274.

Dobbin, F. and A. Kalev (2016). “Why Diversity Programs Fail.” Harvard Business Review 94(7).

Kalinoski, Z.T., D. Steele-Johnson, E.J. Peyton, K.A. Leas, J. Steinke, and N.A. Bowling (2013). “A Meta-analytic Evaluation of Diversity Training Outcomes.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 34(8): 1076–1104.

King, E.B., J.F. Dawson, M.A. West, V.L. Gilrane, C.I. Peddie, and L. Bastin (2011). “Why Organizational and Community Diversity Matter: Representativeness and the Emergence of Incivility and Organizational Performance.” Academy of Management Journal 54(6): 1103-1118.

McKay, P.F., D.R. Avery, H. Liao, M.A. Morris (2011). “Does Diversity Climate Lead to Customer Satisfaction? It Depends on the Service Climate and Business Unit Demography.” Organization Science 22(3): 788-803.

Pendry, L.F., D.M. Driscoll, and S.C.T. Field (2007). “Diversity Training: Putting Theory into Practice.” Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology 80(1): 27-50.