A pivotal moment for SWE Fellow and founding member Alma Kuppinger Forman, P.E., took place when she attended a formal tea held by the dean of women students at Philadelphia’s Drexel Institute of Technology. “It changed my life,” Kuppinger Forman recalled years later when addressing a SWE conference. She noted that in her student days, going to tea meant dressing up and donning hats and gloves.

In the fall of 1945, Kuppinger Forman was one of 11 first-year women enrolled in the engineering program at what today is known as Drexel University. She joined five upper-class women plus another eight enrolled in the engineering school’s evening program. Meeting one another at the tea was the impetus for subsequent gatherings on campus, sometimes over lunch and frequently in classroom buildings that did not have restrooms for women students — typical for the era.

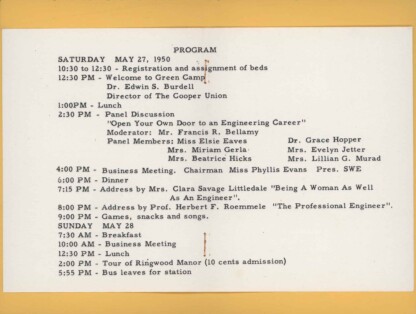

Four years later, in her senior year, Kuppinger Forman chaired a conference organized by the women at Drexel who invited women engineering students from other East Coast schools. The conference organizers called it the “first conference of women engineering students, sponsored by the Society of Women Engineers.” Because the conference included only students and predated the formal founding of SWE, it is no longer viewed as the first conference. It did, however, significantly set the stage for the May 1950 meeting at Cooper Union’s Green Camp of Engineering, where women engineers and engineering students from Philadelphia, New York, and the region spent a weekend “birthing” the Society of Women Engineers.

Joining Kuppinger Forman at Camp Green — as it was affectionately called — were a number of Drexel students and graduates, as well as other women from the Philadelphia area. Between the various speakers, panels, and strategy sessions, there was still time for recreation and bonding through sports and games.

The weekend closed with a tour of nearby Ringwood Manor, a bus to the train station, and the framework for a national organization. Over the next years and decades, dedicated members would work to fulfill the organization’s mission, eventually expanding it across the globe.

That formative weekend, Drexel student Phyllis “Sandy” Evans Miller was on the program to chair Saturday afternoon’s business meeting. At the time, Evans Miller was president of the student group at Drexel, where she had been one of the organizers of the 1949 meeting. Graduating from Drexel in 1950 with a B.S. in mechanical engineering, she went on to become the Society’s corresponding secretary in the early years. It is largely thanks to her writings that we have a clearer picture of SWE’s founding history.

Evans Miller authored a detailed report in 1951 and 1952, at a time when efforts were underway to establish a consensus on SWE’s founding date: Was it the 1949 meeting at Drexel, or the 1950 weekend at Camp Green? The 1950 date was eventually chosen because the gathering included both students and working women engineers.

Unpredictable and profound energies

By 1951, Evans Miller had married, moved to Pittsburgh, and launched her career. Hosting a gathering of women engineers at her home, the group formed the Pittsburgh Section that July, choosing Evans Miller as one of the Pittsburgh representatives to the board of directors. The following January, an article by Evans Miller was published in the Journal of the Society of Women Engineers, volume 2, number 2, titled “Rocket Motors.”

Evans Miller worked in the Atomic Power Division at Westinghouse Electric Corp., where one of her assignments was the mechanical drive train for the Nautilus submarine. Prior to that, she was employed at the Naval Air Development Station in Johnsville, Pennsylvania. Her love of rockets and fascination with the possibilities of human space flight may have placed her a bit ahead of her time, but would prove to have far-reaching effects.

“My mom kept me home from elementary school to watch the Gemini and Apollo launches,” reported David W. Miller, Sc.D., currently vice president and chief technology officer at The Aerospace Corporation and the younger of her two sons. He recalled that when the school phoned regarding his absence, her stern reply was that he was receiving a better education by watching the launch.

He and his brother Jon, an actor in New York, don’t remember their mom working as a mechanical engineer but do recall that, growing up, all family vacations had to include an educational component. “She heavily steered my career in the aerospace field,” Dr. Miller said. During World War II, she was learning to fly and had hoped to be part of the civil air patrol until her father pulled her from the program out of concerns for her safety. “When I turned 16 years of age, she brought me to the local airport and told me it was time I learned to fly,” he said, adding with a laugh, “That evening, my dad sat me down and said it was time for me to learn to pay for it.”

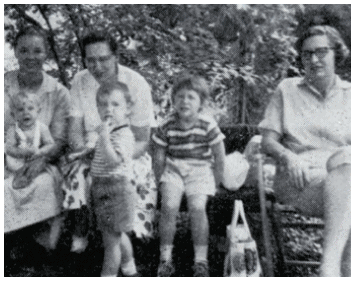

Pittsburgh Section held a picnic the previous August on the farm of Dorothy Rahn, section president. Among those

enjoying the outing were, from left: Phyllis Evans Miller and her infant son, David; Margaret Kipilo and two of her five children; and Constance Craver. It was reported that “those attending brought their own picnic lunches and then shared with the others.”

Dr. Miller attended the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he earned his bachelor’s, master’s, and Sc.D. in aeronautics and astronautics. Prior to joining Aerospace, he was director of the Space Systems Laboratory and the Jerome C. Hunsaker Professor in the department of aeronautics and astronautics at MIT. He remains on the faculty there, on a temporary leave of absence. Additionally, he spent five years, including two as vice chair, on the Air Force Scientific Advisory Board. He also served as NASA’s chief technologist at its headquarters in Washington, D.C.

Relaying an insightful moment with an MIT colleague and astronaut, Dr. Miller shared that the conversation turned to how each had chosen their career paths. When Dr. Miller described his mom’s influence, the response was, “Oh, this wasn’t your career choice.” And Dr. Miller replied, “No, I think you’re right,” adding that “I haven’t regretted it.”

Evans Miller was an advocate of STEAM before the term existed, promoting the arts along with science, technology, engineering, and math. When Jon Miller aspired to earn a Master of Fine Arts with a focus on theater, it seemed that his dream would not come true, and he began law school instead. As it happened, the drama department at Ohio University called at the start of the academic year, offering a late acceptance. Being a lover of the arts and having her son’s best interests in mind, Evans Miller called him to let him know about the offer. Leaving law school, he entered the program, opening the way to his acting career.

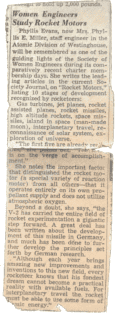

In a touching gesture, Dr. Miller carries in his wallet a 1951 article reporting on his mother’s work. Titled “Women Engineers Study Rocket Motors,” the article references Evans Miller’s feature story on rocket motors in the then-current issue of the Journal of the Society of Women Engineers, and her contributions as a founding member of the Society.

Recently, in what one might call an instance of energies coming full circle, SWE and Dr. Miller were brought together. While a number of women engineers at Aerospace have been and presently are SWE members, the Society’s current president-elect, Rachel Morford, met Dr. Miller at a company event. She was delighted to learn that his mother had been a founding member who played a key role in the Society’s early days.

Two engineers in the house

A large, wooden drafting table in the basement of her childhood home stands out as one of Dianne Forman’s early memories. From there, her mother, Alma (Kuppinger Forman), worked on various consulting projects. “I would sit with her, making ‘rabbit holes’ from a circle template. In the afternoon, when school let out, a neighbor’s daughter would come and take me to the park,” Dianne said.

Alma married E. Ross Forman, P.E., whom she met as a fellow engineering student at Drexel. Before Dianne was born, Alma had been one of two women engineers at Dustin, where she designed turbines. The other woman was close friend and SWE founding member Doris McNulty, P.E. — known as “Aunt Doris” to the Forman children.

Several years later, a brother, Bruce, was born. “With two young children, my mother stopped working but was always active in the community,” Dianne recalled. Eventually, Dianne developed an awareness that her family might be a bit unusual. “With engineers in the house, and both of them proud P.E.s, dinner conversations were different. It dawned on me one night, when the conversation had turned to gear ratios and we were all following it.” Plus, “there was always talk about SWE.”

Additional indicators of a less-than-typical household became apparent when a guidance counselor did not recognize the family’s commitment to higher education and told Alma that Dianne wasn’t college material. “Wrong person to tell that to,” Dianne said. “My mom tutored me in physics that summer using a little chalkboard set up in my bedroom. I learned several valuable math skills that summer that have stuck with me my whole life. By the way, I graduated cum laude from college. I do not recall the name of the counselor in high school but have always wanted to show her my college diploma.”

Thanks to “Aunt Doris” McNulty, Alma embarked on a new career as a college instructor. McNulty was working full time for an engineering firm and teaching nights at a local community college when, in the middle of the term, her company sent her to a job in Italy. Alma was called in as a replacement, and later began teaching at Drexel and eventually ran the engineering computer graphics lab at Temple University. “Though not planned,” Dianne said, “teaching enabled her to actively participate with the new, up-and-coming young women engineers of SWE.”

While they were growing up, the Forman children made firm decisions about future careers. “Both my brother and I were not going into engineering, even though we built forts in the backyard and made buildings with my brother’s girder and panel set. No, we were not going to do what Mom and Dad did,” Dianne said. Things turned out differently, however. “In my adult life, I ended up working as an electrical designer for an AE firm, while my brother went back to college and got a second degree in mechanical engineering and has had an engineering career.”

Dianne noted that once she became an adult, from time to time she would come across information concerning a renowned woman engineer only to discover, with some surprise, that it was someone her mom knew.

Pride across generations

Gaetana (Tina) Melilli Walecki was still a student when the Camp Green meeting took place. She ended up transferring from Drexel to Temple University because the radio and television portions of Drexel’s electronics engineering program were discontinued. While at Temple, she worked on the production of the UNIVAC at Eckert-Mauchly Computer Corp. and graduated in 1952. After marrying and having children, in 1964 she went back to work at Beckman Instruments in Cedar Grove, New Jersey, where she developed her own inventory system for all the instruments the company built.

Walecki’s daughter, Patti Walecki McCormick, her grandson Timothy McCormick, and granddaughter Caroline McCormick individually shared memories and perspectives with the SWE archives. “She was always proud that she worked on the very first computer,” for business applications, Patti wrote. “Through the years, we heard many stories of what it was like to work with such men as Pres Eckert and John Mauchly. Grace Hopper, too. As kids, we really didn’t understand what she did, but we understood that it was a special thing to be a woman in engineering back in those days.”

Regarding the impact her mother’s career had on the family, Patti wrote:

“It certainly influenced me and my sisters on women’s roles. She was a role model for us and told us we could be whatever we wanted to be … As for women’s rights, the one thing I remember her saying over and over was, ‘Because you’re a girl, you’re going to have to work twice as hard to get half as far as a man.’ She said it matter-of-factly; there was no complaining or bitterness. If I would complain about the seeming unfairness, she would just say, ‘That’s the way it is.’”

Patti was very proud of her mother but would have preferred to have her home and more available, which led her to decide against having a career. Instead, she worked part time while raising her four children. “I have no regrets,” she said, adding that:

“I’m still very proud of what my mother accomplished. As for her grandchildren, that’s another story … Her legacy influenced several of her grandchildren to attend and graduate from Drexel University. Two grandsons are engineers; one granddaughter and one granddaughter-in-law graduated with engineering degrees. Two grandsons are computer programmers, and one granddaughter became a teacher. All graduated from Drexel and, I think, were directly influenced by their grandma.”

Grandson Timothy McCormick, P.E., was working as a civil engineer in Florida when he reached out to the SWE archives several years ago, identifying his grandma in the iconic group photo taken at Camp Green and hoping to frame a copy as a gift to her. He updated SWE’s records with some recent details on her life.

Like her mother Patti, granddaughter Caroline McCormick responded to a survey issued by the SWE archives and SWE Magazine during the 70th anniversary year. “I didn’t talk to her much about her work growing up. It wasn’t until I started looking at colleges and majors that my family told me about her important contributions to engineering,” she wrote.

Learning about her grandmother’s accomplishments “was inspiring,” she added. “I wasn’t sure if I could do it, as everyone else in my family that had gone to Drexel for engineering had been male, but if she could do it, I knew I could do it.”

In terms of the impact her grandmother had on her views of women’s roles and women’s rights, Caroline wrote:

“She was always very strong willed and did not back down from any challenge. She let her opinion be known and was proud of her accomplishments. I think that made me more confident in my decisions and look at women as stronger figures than maybe I would have otherwise. I ended up going to Drexel for materials science and engineering. Two of my cousins and my brother went to Drexel before me, and then several other family members went to Drexel following me.”

Caroline summed up her grandmother’s influence: “She inspired me to take a chance on myself, to not be afraid to take on a profession in a male-dominated industry, and to stand up for what I believe in.”

The Biggest TV Set in South Philly

Patti Walecki McCormick shares a family story that her mother was fond of telling. “While working at Eckert Mauchly, she met the man who was to become our dad. They worked on some very tedious project together and decided they were compatible. As a courtship project, they ordered an RCA TV kit to assemble together. They adapted it to a bigger CRT screen, and my grandfather (Mom’s dad) built a cabinet for it from an old Victrola cabinet. They were very proud of their project, but no one was prouder than my grandfather of his daughter, the engineer! The entire neighborhood would come over to watch the biggest TV set in South Philly. In fact, when Mom and Dad married, my grandfather insisted on keeping the set. I think he just wanted to continue to show friends and family what a smart daughter he had.”

Patti Walecki McCormick shares a family story that her mother was fond of telling. “While working at Eckert Mauchly, she met the man who was to become our dad. They worked on some very tedious project together and decided they were compatible. As a courtship project, they ordered an RCA TV kit to assemble together. They adapted it to a bigger CRT screen, and my grandfather (Mom’s dad) built a cabinet for it from an old Victrola cabinet. They were very proud of their project, but no one was prouder than my grandfather of his daughter, the engineer! The entire neighborhood would come over to watch the biggest TV set in South Philly. In fact, when Mom and Dad married, my grandfather insisted on keeping the set. I think he just wanted to continue to show friends and family what a smart daughter he had.”

The TV set remained in the family until recently, when it was donated to the InfoAge Science and History Museum in Wall, New Jersey.