What, in your opinion, are the most exciting recent developments involving the archives?

Perhaps the biggest thing that excites me is that the number of reference requests I receive has more than doubled over the past four years. I logged 62 reference requests in 2015, and 153 in 2019. Additionally, some of the requests I receive have become far more complex. While I still get routine requests for biographical information, photo searches, or basic fact checking, I’m now being asked to provide background on the origin and evolution of various SWE policies and procedures and the issues past SWE leaders considered in weighing their options — all to better inform current and future decision-making.

The increase in these kinds of questions is coming both from members of SWE’s professional management team and volunteer leaders. Some of the interest is a result of my being here for more than a decade, building relationships with them, and encouraging them to ask these types of questions.

I’ve received requests from SWE leaders that suggest they see how understanding why decisions were made a certain way in the past will help them make better decisions in the future. Likewise, SWE staff members have come to appreciate how the archives can support headquarters operations in ways that, while not always exciting or inspiring, are still useful and can make their work easier.

This excites me! The archives is doing exactly what an archives should be doing — using the past to inform the future.

In recent years I’ve also provided images and information and research to journalists, scholarly writers and children’s authors, and (amateur) screenwriters.

In what ways is the digital age impacting your work? Has it been a positive or negative influence and why?

The digital age has added complexity to archivists’ jobs. Many of the principles regarding digital and paper records are the same, but digital records are more complicated and present more problems.

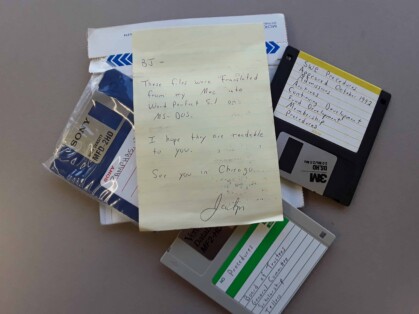

With paper, you just need eyes, a source of light, and, perhaps, a magnifying glass to read a document. Electronic records require appropriate equipment to read the media (like a 3.5-in. floppy drive, a CD-ROM drive, a USB port, etc.); the necessary software to read the file type (particularly proprietary file types from companies long out of business); digital forensics tools to determine if the file has been corrupted over time; and perhaps other software to migrate the file to a more readable format.

Newer generations of archivists are pretty comfortable with this complexity, however, because they’ve grown up with the technology and have been training for it in their classwork. Oddly enough, it’s the older, analog stuff that throws them.

Last week, while I was visiting a Facebook group for archivists, a young woman asked for help identifying an object she had found in a collection. It was a 35mm roll of camera film. She had never seen one before. I told her what it was, laughed hysterically, but also felt about a million years old!

The digital age has made gathering and donating archival files both easier and harder, at the same time, which is quite a feat. With paper-based archives, people tend not to forget that they have a box or two of worthwhile documents for the archives because they are physically in the way. You get tired of tripping over a box of old stuff, or moving it from one box or another. But, you can easily ignore and forget files sitting on your computer, because they probably aren’t inconveniencing you. There are lots of ways for files to get lost — people may do some things on their work computers and some things on their home computers, replace their computers over time, have hard drives crash, put files in cloud storage accounts that they later forget about, etc.

It’s the ease with which people can forget about their computer files that helped contribute to widespread losses of archival records at the dawn of the home computing era. But, once someone does locate the files they wish to donate, it’s quite easy to transfer the records to the archives. Members can just drop their files into a folder on a cloud storage service, send me the link, and I can download them to our digital preservation environment. We have other transfer options to handle more security-sensitive files, too. And, I can see and consult in real time on the files they upload.

What types of digital communications technology have you used to share SWE history and raise the archives’ public profile? How successful has it been?

I’ve been sharing archival content in a SWE Magazine column titled “Scrapbook” for years. I’ve extended the archives’ reach into the digital realm more recently. About a year ago, I created a Twitter account so I could share some of the “fun finds” I come across when doing research in the collections. Sometimes, I post things I find that make me think (https://twitter.com/TESquaared/status/1189578573629263873). Sometimes I post things that SWE did in the past that are still valid today (https://twitter.com/TESquaared/status/1184894126229086209 or https://twitter.com/TESquaared/status/1179055272301486080). And sometimes I post things just because I think they’re funny (https://twitter.com/TESquaared/status/1189926335151366146).

In 2017, SWE Director of Editorial and Publications Anne Perusek and I began to collaborate on “Tales from the SWE Archives,” a podcast that airs, periodically, on SWE’s Diverse podcast. This year, it received a FOLIO award. It takes time to produce an episode, but I have great fun doing the research and sharing the great stories buried within the archives. And, I appreciate talking over the topics with Anne, because she brings fantastic institutional memory and helps me to refine my thoughts and make connections that I might not make on my own.

In July, we did two episodes on SWE members who contributed to the first lunar landing, including audio excerpts from some of their oral history interviews: https://alltogether.swe.org/2019/07/podcast-series-one-small-step-for-man-one-giant-leap-for-woman-engineering-kind/.

Extending the Life Spans of Archival Materials

Shortly after noon on Dec. 7, 1978, three explosions rocked the National Archives warehouse, in Suitland, Maryland, igniting an immense blaze that burned out of control for more than an hour. By the time it had been put out, 12.6 million feet of priceless newsreel footage — enough to stretch from New York City to Reno, Nevada — had been destroyed.

The lost newsreels, which had been stored in fireproof, climate-controlled vaults, contained never-before-seen outtakes from the Great Depression and World War II — including scenes from the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. Everything had been shot on highly volatile nitrate film — a material that decays rapidly and grows increasingly more flammable over time. It turned out that the film could spontaneously combust at even lower temperatures than experts predicted.

All archival materials deteriorate and will ultimately fail, though rarely in such sudden and spectacular fashion. Most paper records, such as those stored in the SWE archives, will slowly fade away, if stored at room temperature. Signs of aging typically appear at about 39 years, say Chris Cameron and Kelly Krish, preservation experts with the Image Permanence Institute (IPI), a nonprofit technical group at the Rochester Institute of Technology.

IPI develops custom preservation plans that cost effectively extend the lives of physical archival materials. Krish, a preventive conservation specialist, assesses the collection’s preservation needs, while Cameron, a sustainable preservation specialist, evaluates the capabilities of the building’s mechanical system. Then, Cameron said, “We meet in the middle and see what’s realistically possible for the collection.”

In most cases, they said, it’s possible to keep paper items in good condition for 100 to 110 years. This typically requires eliminating exposure to such “agents of deterioration” as water, UV light, fire, animal and insect infestation, and air pollution — and to maintaining year-round temperatures near 70 degrees Fahrenheit and relative humidity at around 50%. If they can use a combination of cold storage and custom-designed storage space, they said, it’s possible to keep paper in near-pristine condition for up to 500 years.

Digital records, on the other hand, are far less stable and exhibit a fragility that has more in common with nitrate film, minus the tendency to explode or burst into flames. Sean Ferguson, a preservation specialist with the nonprofit Northeast Document Conservation Center, promotes digitization as a method to preserve paper and audio records by greatly reducing the need for physical handling of original materials.

Digital files acquire much of their stability from the storage media they’re saved to and are susceptible to a broad range of threats: everything from random data integrity losses, called “bit rot,” to data loss from viral attacks, obsolete software and hardware, outdated file formats, hard drive crashes, and more. These are often total, irrecoverable losses.

“Putting image files on a hard drive and letting them sit there is not an acceptable solution over the long term,” Ferguson said. “Hard drives tend to have failure rates that accelerate after about five years. If you’re not routinely checking the files, the results can range from not a huge problem to potentially catastrophic.”

What special projects are you currently working on or contemplating?

I have many, many projects that I would like to do in the future, but with so many in-depth reference requests to fill, it’s hard to carve out the time! I’m excited about the next few archives podcasts. I recently rediscovered a recording of seven early SWE Achievement Award recipients who spoke during a panel at the 1968 SWE national convention (as they were called at the time). I found and digitized the audio reel shortly after I became SWE’s archivist in 2008 but the sound quality wasn’t great, and since I was new I didn’t fully appreciate how remarkable the content is. I recently listened to it again and was astounded. Having worked with SWE’s archives for more than 11 years, it was thrilling to hear the voices of these amazing women I’ve come to know and admire only through paper and photographs — including Bea Hicks, SWE’s first president. Listening to them speak, I learned that not only were these ladies brilliant, but they were also very, very funny. We’ll be featuring their speeches in a few Tales from the Archives podcast episodes this winter and spring.

I also want to digitize all back issues of SWE Magazine and its predecessors (U.S. Woman Engineer, SWE Newsletter, Journal of the Society of Women Engineers). I use them constantly for research, so it would be greatly useful to me, but I also think members would enjoy reading about what SWE was up to 70 years ago. Outside researchers will appreciate it, too. It will be a time-consuming project and will likely span a few years, whenever I have a few free hours to scan, add metadata, and so on. There are a lot of other projects I must do or would like to do, but those are probably the most interesting!

After the digital revolution took hold in the mid-1990s, the number of new paper records being created fell precipitously. How has the rise of digital records affected you? Do you still cross paths with paper-based records?

Believe it or not, I still receive paper-based records, mostly from SWE members who have held leadership positions in old regions or on committees. I received about 10 such shipments in 2019. They typically come in a single envelope or a small box, and often measure no more than half a linear foot.

On occasion, I still get cool things, too! At WE19 in Anaheim, Past President Penny Wirsing, F.SWE, gave me a matted collage poster presented to the Los Angeles Section by former NASA astronaut Bonnie Dunbar, Ph.D. Dr. Dunbar was a SWE Achievement Award and Resnik Challenger Medal recipient, and a senior member of SWE, who co-chaired the 1981 SWE national convention in Anaheim.

The collage poster Dr. Dunbar donated included photos from the 1998 shuttle mission STS-89, on the shuttle Endeavour. It has the STS-89 crew patch attached to the collage — and a small U.S. flag that went into space on the shuttle Columbia during STS-50 in 1992 (which Dr. Dunbar also flew on). It’s large, so I had to bring a big suitcase to the conference so I could bring it back home.

I already had another collage poster from Dr. Dunbar’s STS-32 mission in 1990 in the archives. Also, the flag on the collage is the second item in the SWE archives that has been to space; the first is Dr. Dunbar’s Resnik Challenger Medal, which she took with her on STS-89 and donated back to SWE afterward.

We have a lot of amazing, historically rich collections here at the Reuther Library (comprising some 75,000 linear feet), but I get bragging rights for having the only collection in the building containing not one, but two, objects that have been in space.

How will you and the archives be involved in celebrating SWE’s 70th anniversary? And to what extent, if any, does this represent a departure from the way the archives has supported past celebrations?

SWE launched the beginning of its 70th anniversary celebrations at WE19. I selected a few historic photos from SWE’s archives to be offered as backdrops in SWE’s photo booth at the conference. We used green-screen technology to take the members’ pictures and then insert them directly into the Founders Day images. They leave with pictures that literally place them at the heart of SWE history. I worked with the marketing team on a short sneak-peak video launched at the conference, to highlight seven decades of SWE. Throughout the year, we will collaborate on more in-depth videos that present each decade’s SWE history. As always, I will be working with Anne and various SWE Magazine writers, helping them research stories exploring SWE history. One article in the conference issue of the magazine details the history of SWE’s awards program, highlighting the initial recipients of each award. There will be a few surprises, which are still in the works, and, we’re already talking about the 75th anniversary, in 2025!

How much of SWE’s born-physical (paper) archives would you like to digitize? What are the main constraints? And do you think the archives might ever become a fully digitized, online resource?

Sadly, digitization is not the silver bullet we all wish it was. It would easily cost many tens of thousands of dollars to digitize SWE’s paper collections. Perhaps many, many tens of thousands of dollars.

It’s a slow process. You must remove staples and paper clips. Some documents are bound and must be scanned page by page. Some things are oversized, and you must scan different quadrants and piece the images together in Photoshop®. And, you can’t just throw everything in a scanner with an automatic paper feeder, because some of the older documents in SWE’s collection are on brittle paper that crumbles if it goes around the roller on an automatic feeder.

A sizable number of the documents in SWE’s archives are carbon copies printed on onionskin (i.e., very thin paper), and automatic feeders tend to crumple or tear onionskin. There are also a lot of corrected copies of board minutes, where corrections have been cut and pasted over the errors. That glue has gotten very brittle over time, and were I to run those through a document feeder on a scanner, the glue would fail and the corrections would fall off. And, probably, the little bits of paper would get stuck in and jam the scanner.

An archival collection like SWE’s must be scanned page by page, which is a slow process, even with a fast scanner.

While I would love to do it in the long term, currently there are no plans to digitize all or large parts of SWE’s archives. We would have to send the collection out to a vendor to do the work. That’s very expensive, and parts of the collection would be inaccessible for many months. But, in the short term, I want to finish scanning SWE Magazine and its predecessor publications, because they are fantastic research tools and fun to read. It’s at a scale that I can handle myself.

I should mention that microfilm is still considered the preservation standard, because all you need is a source of light and a magnifying glass to read it, and when stored in the proper environment, the film can last for a few hundred years.

While digitizing documents for preservation is a worthwhile endeavor, it doesn’t necessarily make the documents any easier to find. You can run the resulting PDFs through optical character recognition software to increase word searchability, but in an archival collection like SWE’s, the results will vary widely.

OCR software will do mostly fine on documents from the past 30 years, but the software often struggles with documents printed or typed with older fonts and inconsistent character spacing. Onionskin copies are usually a bit blurry and stymie the software. And then there’s all the handwritten documents … some of which are very difficult for me to read and understand, too!

SWE’s New Data Governance Effort Is Particularly Good News for the Archives

Last August, SWE expanded its ongoing data governance work, by adding research and data management oversight to its membership department, which is run by Honna George, the director of membership and data management.

George has been involved, to one extent or another, in shoring up SWE’s data management capabilities since she first joined SWE in the spring of 2015. Her efforts have included building and leveraging a SWE salesforce environment to track and manage SWE’s organizational sponsorship and partnership activities, consolidating 15 years of fragmented data sales into a single database.

In June, George and Roberta Rincon, Ph.D., SWE’s senior manager of research, worked with DelCor to assess SWE’s current data governance needs and practices, especially with regard to data of its members. Results from this work will be implemented through SWE’s data governance work group, which began in 2017 and has been led by Dr. Rincon. “We are aggressively pursuing technologies that will allow us to increase our capacity to keep core member information within the root member record,” George said.

Through the examination of SWE’s data practices over the past few months, George, Dr. Rincon, and others identified the need for guidelines to ensure the smooth flow of electronic records to the archives and to involve the archives directly in future decision-making that could affect it. “As SWE evolves its relationship to maintaining the integrity and privacy of its member data now and in the future, Troy Eller English will be involved and asked to provide input, from an archival perspective, about what data to retain,” said George.

Such engagement should help avoid another “lost decade” — Eller English’s term for the period from 1994 to 2004 when the rapid switch to personal computing caught most archives, and the institutions they serve, off guard. Back then, few, if any, parent organizations had any guidelines or procedures for preserving their paper records, let alone the digital files that rapidly replaced them. The resulting loss of valuable records was substantial, and archives everywhere have scrambled to make up for the loss.

Eller English devoted a great deal of time and energy into finding — and compiling — substitute sources of information to fill in the gaps.

“Combined with information contained in minutes from the board of directors and senate, back issues of SWE Magazine, and whatever else I can find,” she said, “I usually can provide at least some basic information for whatever topic I’m asked about.”

What archival records are currently accessible to SWE members online? And what plans do you have to provide additional online access in the future?

Currently, just the American Society of Women Engineers and Architects Records (http://reuther.wayne.edu/node/3179) and selected SWE photographs (http://reuther.wayne.edu/image/tid/5) and audio files (http://reuther.wayne.edu/search/node/type%3Aaudio+category%3A22+Engineers). The university is in the process of hiring two positions (a librarian and an archivist) with shared responsibilities for building a robust digital repository to handle both digitized and born-digital collections.

The next thing I would like to put up would be the old SWE publications. In addition to technical challenges, there are also copyright and privacy concerns to consider. I would love to scan all the old news clippings files, because those are fun, but copyright becomes a problem. You can only skate by on fair use claims for so long.

The 70th anniversary content will almost certainly be available online. The marketing team will be making short videos highlighting each decade of SWE, which will be accessible and shared online. Anne and I will probably do a podcast or two. The magazine articles will be posted on alltogether.swe.org.

Where is the archives currently benefiting SWE the most, and how do you see that changing?

I think different constituencies within SWE would see the archives as having different impacts, because they have different concerns. For the past several years, SWE’s marketing team has really seemed to connect with the archives. They have a message to get across, and the archives help them to do that. SWE has been there, supporting women engineers for the past 70 years, it is here today, and it will be here in the future. As I mentioned earlier, I’ve received requests from SWE leaders over the past year that suggest they are seeing how understanding why decisions were made in the past will help them make good decisions now and in the future.

What technological advances are you most excited about for their impact on the archives? How will they change things?

It feels like for the past 20 years, archivists and researchers and digital preservationists interested in electronic archives have been throwing cooked spaghetti at the wall, seeing what will stick. It feels like we’re finally getting to the point where the spaghetti is sticking … we’re making progress! There are digital preservation platforms available to make it easier to read and understand those files in ancient file formats; there are digital asset management and digital repository platforms; there are cheap computers and plug-in 3.5-in. floppy drive readers; and the number of people who understand and can use those systems is increasing. But the challenge for any archives is now, and will always be, finding the time and the money and the willpower to implement all that.