“Bringing Gender Equity to Space” was originally published on thebossmagazine.com.

Space: the final frontier. We’ve called it that since “Star Trek” popularized the phrase in the 1960s. Captain Kirk’s opening monologue recited the Enterprise’s mission “to boldly go where no man has gone before.” But it wasn’t just men aboard the Enterprise. Several women played key roles on board, and “Star Trek” was ahead of its time in social commentary and showcasing people of color. It was also well ahead of the real-life space program at NASA. In the intervening decades, a lot has changed on that front, but there is still plenty of work to be done. Space might still be the final frontier for gender equity.

It’s the Little Things

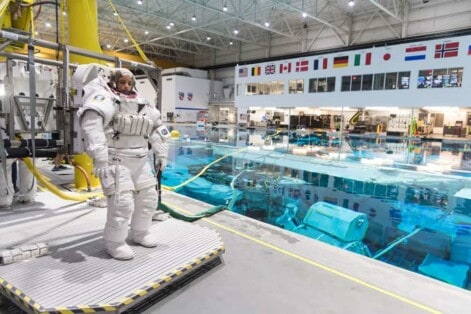

In the spring of 2019, Anne McClain and Christina Koch were set to perform the first all-female space walk outside the International Space Station. Then a problem arose: Both fit better in medium-sized upper torso spacesuit assemblies. While there were two mediums aboard, only one had been prepped for a spacewalk. Instead, Nick Hague replaced McClain on the walk.

Depending on your perspective, you might see the incident as an amusing “wardrobe malfunction” and joke about our ability to walk in space but not have enough gear in the right size. Or, you might see it as another sign of how institutions default to accommodating men and make gender equity an afterthought. NASA spacesuits come only in medium, large, and extra large. When a technical glitch forced a redesign in the 1990s, none of the astronauts on the roster at the time needed a small. So they just never made one. As McClain’s case shows, they’re not exactly flush with mediums, either. To be fair, the suits cost millions of dollars to make, but budget decisions often are hidden factors that reinforce unequal representation in institutions.

Koch and Jessica Meir eventually performed the first all-female spacewalk last October. Those three women, along with Nicole Mann, were part of the historic Astronaut Group 21 class in 2013. The group has four men and four women, the first time a NASA astronaut class featured as many women as men. The 2017 class, Astronaut Group 22, brought in another five women astronauts out of 12 total. These are monumental steps, to be sure, but of the 48 astronauts NASA lists as eligible for flight assignment, only a third are female.

Giant Leaps

When the Mercury Seven, NASA’s first class of astronauts, were announced in 1959, they were all active duty military test pilots. John Glenn and Alan Shepard were two of the famous names among them. Since women weren’t allowed to be military test pilots, none of the more than 500 candidates considered was female. Gender equity wasn’t even a possibility. It wasn’t because women couldn’t do the job. In fact, Randolph Lovelace, the doctor in charge of examinations for the Mercury Project, began testing female pilots in 1960. Of 19 women he tested, 13 passed—a better ratio than the 18 of 32 men who passed Lovelace’s tests.

Lovelace’s reasoning for testing women was still pretty sexist. He was looking for potential space secretaries, telephone operators, and lab assistants, Margaret Weitekamp, author of Right Stuff, Wrong Sex: America’s First Women in Space Program told The Atlantic. But when the Soviets successfully sent Valentina Tereshkova on a solo mission in 1963, the myth that women couldn’t be astronauts was pretty much busted. It would still be another 20 years before the US sent Sally Ride into space, however. As Congresswoman Clare Boothe Luce put it in 1964, “The US could have been first to put a woman up in space simply by deciding to do so.”

Sixty years after Luce’s statement, NASA’s Artemis program aims to put the first woman on the moon. The name is symbolic. In Greek myth, Artemis was the twin sister of Apollo, namesake of the program that put the first men on the moon. While symbolism is good, achieving gender equity in space will require more than symbols. It will require more breakthroughs like Astronaut Group 21 and putting women on the moon.

STEM Diversity

Getting more women into space—or even into control rooms on Earth—starts with STEM education and hiring practices. The National Science Board found that in 2015, of the people in the workforce whose highest degree was in science & engineering fields, 40% were women. Yet women made up 28% of the science & engineering workforce. Both figures were trending positively from 1993. But in engineering, physical science, and computer/mathematical science fields, men still make up a large percentage of the workforce.

Achieving gender equity means hiring more women in these fields and encouraging more girls to enter them as students. Each year, Delta Airlines flies an all-female crew to Houston with a plane full of girls headed to NASA for International Girls in Aviation Day on Oct. 5. Last year’s flight brought 120 girls from Salt Lake City to tour NASA.

“When I was little, I was good at school, but they told me I should become a doctor or a teacher,” Farah Alibay, an aerospace engineer at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Los Angeles, told the Huffington Post. “We never tell little girls that they should become engineers or astronauts.”

Alibay is part of the team that sent the Perseverance rover to Mars in July. The engineers who never leave the ground are just as vital to the success of missions, and they are beginning to get their due with the renaming of the NASA’s Washington, D.C., headquarters after Mary W. Jackson. She was NASA’s first Black female engineer and depicted in the book and film “Hidden Figures.”

Gender equity is not the only imbalance that can be shifted. Racial inequity in space is also an issue.

“It is still unbelievable to me that we have flown only 11 Black males and three Black females in space out of 350 U.S. astronauts,” former NASA deputy administrator and Brooke Owens Fellowship founder Lori Garver told Space News. “It’s shameful.”

The fellowship’s efforts have helped lead to Virgin Galactic’s pledge of a $100,000 scholarship for Blacks pursuing aerospace-focused STEM degrees.

Jus as diversity brings more success to the boardroom, it does so in charting the final frontier.

This article was originally published on thebossmagazine.com.

Related content:

- A Day in the Life of An Aerospace Engineer

- Making “HERstory” with First All-Women Spacewalk

- Finding Beauty—In Space and on Stage

- Two Women Are Spearheading Chandrayaan-2, India’s Latest Space Mission

- Spacecraft Engineer Renee Frohnert Celebrates Apollo 11’s 50th Anniversary

- The Space Engineers Tackling Gender Inequality

Author

-

SWE Blog provides up-to-date information and news about the Society and how our members are making a difference every day. You’ll find stories about SWE members, engineering, technology, and other STEM-related topics.