2020’s election cycle was one for the history books — from the highest voter turnout in more than a century to a surge in mail-in voting, to the throes of a pandemic, it won’t soon be forgotten.

And it was historic as well for the records it set for women’s representation in Congress and in the White House.

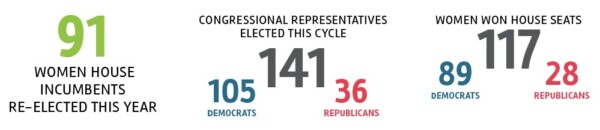

U.S. congressional representatives elected this cycle include at least 141 women — 105 Democrats and 36 Republicans. This surpasses the previous record of 127, which was set in 2019, according to research by the Center for American Women and Politics (CAWP) at Rutgers University. (At presstime, there were still races with women candidates that hadn’t been called.)

Many who track politics wondered whether 2018’s record-busting election year was a trend in growth for women’s representation in politics, or an anomaly. 2020’s results show it’s a trend that’s continuing, albeit with gains that aren’t as substantial.

Much of the surge of elected women came from the Democratic party in 2018, while the Republicans declined in female representatives that cycle — from 23 to just 13 — including only one new woman representative to the House.

This year, more of the growth in women’s representation comes from the Republican party, which had a record year for women elected to the House. The Democrats, meanwhile, didn’t surpass their 2018 record.

“I’d be cautious to say this was a good year for Republicans all around, but it was a better than expected year for them,” said Kelly Dittmar, Ph.D., director of research at CAWP. Pre-election forecasts were wrong, and Republicans won more of the competitive seats they weren’t favored to win.

The Republican women officeholders in Congress will still be outnumbered by Democratic women, and they will still be underrepresented, but their outcome is notable nonetheless for not only making up for their losses from 2018, but also in adding more women overall to their ranks.

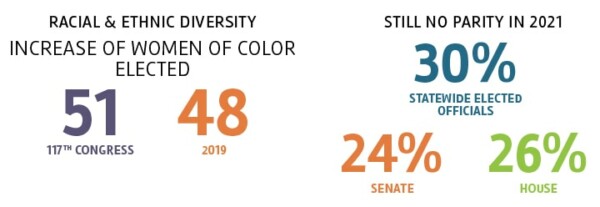

In terms of racial and ethnic diversity in the women elected this cycle, at least 51 women of color will serve in the 117th Congress, surpassing the previous record of 48, set in 2019.

A record number of women in the house

To date, 117 women won seats in the U.S. House this cycle: 89 Democrats and 28 Republicans. The previous record of 102 was set in 2019. This also sets a new record for female Republicans in the House, beating 2006’s record of 25.

At least 91 women House incumbents won re-election this year. Five women House incumbents — all Democrats and freshman legislators who had flipped their districts in the 2018 midterms — were defeated.

“What we saw in the last two cycles is a large proportion of the women candidates running in especially competitive districts,” said Dr. Dittmar, “so it’s not shocking that these women elected in 2018 were going to be most vulnerable this year. There’s good and bad about having women win in these competitive seats: The gain is you are able to take advantage of these moments. The risk is if they’re not in safe seats, there’s more vulnerability when we get to the next election.”

In the 117th Congress, at least 17 Republican women will join the incoming class of new House members — exceeding 2010’s record number of nine and greatly improving their 2018 results. The party’s gain of House seats was due in large part to the success of female candidates. And while there’s a notion that women in the Republican party tend to be more bipartisan or willing to compromise, Dr. Dittmar notes that is not true this cycle.

“They are all very conservative,” she said. “There’s really not a moderate among them.”

This includes gun-rights advocate Lauren Boebert and Marjorie Taylor Greene, who has been tied to the QAnon conspiracy.

The Democratic party also elected several new members who are far-left-leaning, including Cori Bush, elected from Missouri as the state’s first woman of color and first Black woman in Congress.

“She comes from an explicitly activist background, and you’re going to see that, and you’ve already seen it in her attention to Black Lives Matter. She was really on the front lines in Missouri after Michael Brown’s murder, and so she will bring that perspective for sure,” said Dr. Dittmar.

Washington joins Missouri in sending its first Black woman to Congress with the election of former Tacoma Mayor Marilyn Strickland. And the delegation from New Mexico has been noted as a historic all-women-of-color delegation.

Overall, women of color set a new record in the House, winning 48 seats — beating the previous record of 44.

A setback for women in the Senate

Within the Senate, seven women were elected in 2020: two Democrats and five Republicans. Six were incumbents winning re-election.

And while 18 incumbent women senators did not face re-election in 2020, Kamala Harris’ win as vice president brings that number down to 17. This means the Senate will include 24 women: 16 Democrats and eight Republicans. The record number of women in the Senate was 26, set in 2019. In a January runoff, Sen. Kelly Loeffler, a Republican, lost the seat she was previously appointed to.

None of the women elected to the Senate this year were women of color. The three women of color returning to the Senate — Tammy Duckworth, Ph.D.; Mazie Hirono, J.D.; and Catherine Cortez Masto, J.D. — were not up for re-election this year. And, before her election as vice president, Kamala Harris, J.D., was the only Black woman serving as a U.S. senator.

“It’s striking,” noted Dr. Dittmar, “that we could have one of our top legislative bodies with no Black women in it. Of course, that’s not that odd in U.S. history: Only two Black women have ever served in the Senate.”

A substantial first for the White House

One of the most notable political stories from 2020 was Kamala Harris’ election as vice president — becoming the first woman, the first South Asian, and the first Black American to serve in the position.

“The same positive effects that we point to when we talk about women’s representation apply here, but at an amplified level,” said Dr. Dittmar. “It creates a sense of possibility, it makes individuals and constituencies perceive the institution as more accessible to them, and it has substantive effects — because you bring to the table somebody who has lived experiences and perspectives that are different than all of the white men who have come before her.”

Dr. Dittmar also notes that Harris is likely to expand representation in the executive branch by hiring a diverse staff.

And Cynthia Richie Terrell, founder and executive director of the organization RepresentWomen (formerly Representation2020), points out another important aspect of Harris’ election to office. “Other countries have been shocked that the U.S. has done such a poor job of electing women and people of color. It really undercuts our authority globally when we have such unrepresentative elected bodies. Having a woman in power will not only help in an actual way by bringing more diplomacy and lived experience, but it will also help to set the stage and legitimize women in power in other countries as well.”

Still not near parity

For the record-setting year that 2020 was, there’s still some sobering news. In 2021, women will be about 30% of all statewide elected executive officials, 24% of the Senate, and 26% of the House. Many states have still never had a woman governor, senator, or representative.

“It’s been fairly slow and incremental change for women’s representation over the decades,” said Dr. Dittmar. “Yes, we’ve made gains and they’re not insignificant, but we’re still far from parity.”

In fact, Terrell breaks down the election results in these terms:

• 97 of the 107 incumbent women running won: a 97% success rate.

• 17 of the 44 women running in open-seat races won: a 39% success rate.

• 171 women — the vast majority of women candidates — ran as challengers. And just 10 won — a 6% success rate.

“A success rate of 6% is not encouraging,” said Terrell. “That just isn’t an efficient way to get more women in office.”

The United States’ rate of 26% women in the House of Representatives puts it in 70th place globally for percentage of women in its lower house of parliament — in line with such countries as Bulgaria, Iraq, Afghanistan, Kazakhstan, and Mali.

RepresentWomen looks at best practices around the globe for reaching gender parity in elected offices. Beyond simply trying to encourage more women to run, it’s identified systemwide changes that might be more efficient in reaching gender parity in U.S. politics.

One notable reform it champions is ranked-choice voting: a departure from the United States’ main winner-take-all system that results in plurality winners and split votes among like-minded candidates and like-minded voters. Ranked choice allows voters to rank candidates in order of preference.

Research shows that in ranked-choice voting districts, more women make it through the primaries and then on to run in open seats. Within major U.S. cities that use ranked choice, about half of the mayors and city council representatives are women.

“In terms of changing the voting system, it’s probably the quickest way to increase the number of women, the number of people of color, and the number of younger people serving in office,” said Terrell. And it’s gaining traction: Five states used it in 2020 in their primaries, 19 cities use it nationally, and New York City will be using it for its next primaries. Most noteworthy is the fact that Maine is the first state to adopt ranked-choice voting for all state and federal elections — perhaps a harbinger of more to come.