“That’s What I Wanted to Do” was written by Anne Perusek, SWE Director of Editorial and Publications. This article appears in the 2019 Conference issue of SWE Magazine.

When speaking of her art education at the Cleveland Institute of Art, and desire to be an artist, Jeanne Brodie repeated, “That’s what I wanted to do.” It has been a desire powerful enough to last decades.

Sitting in her comfortable apartment with two daughters at her side, Brodie shared reflections and memories of her nearly 100 years. Her watercolor paintings and sculptures adorned the room, and sunlight streamed in from the patio doors. It was a beautiful morning, and the atmosphere was conducive to lengthy conversations. Still living independently in a senior independent living facility, Brodie was enjoying the moment, while her family was beginning preparations to celebrate the upcoming centennial of her birth.

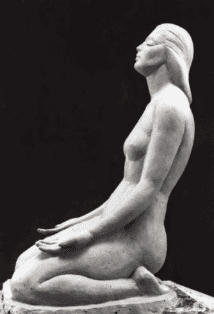

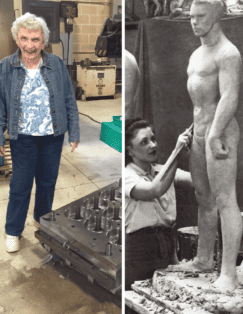

Finally retiring from her work as an engineer at age 97, Brodie remained dedicated to her artistic endeavors throughout those long years. Graduating from the Cleveland Institute of Art in 1941 with a major in sculpture and a minor in watercolor painting, Brodie discovered, quite by chance, a new love in engineering. But she never lost her enthusiasm for art, her trained eye, and the abilities she honed as an art student.

Merging art and engineering on some level, Brodie explained that, “the sculpture, I think, helped me,” adding, “my [engineer] boss used to say I had more vision than most of the men, because I could see around things.”

FORMATIVE YEARS

Women were just winning the right to vote in December 1919 when Brodie was born in northeast Ohio. An only child, her father was a draftsman and for a time ran a hardware store. In keeping with the era, her mother took care of the home and domestic activities. The family purchased a farm with 20 acres in what is now Willowick, Ohio, and became farmers. When Brodie learned to read, her father took the unusual step of teaching her to read blueprints, a skill that became useful years later.

Brodie attended Willoughby Union High School, where, she recalled, “I took all the math I could get, which turned out to be fortunate later on.” She also took art classes throughout high school. “I started with the art teacher, in my freshman year, because I was going to go to the Cleveland Institute of Art.” She graduated in 1937, at the height of the Great Depression. Still, she enrolled at the Cleveland Institute of Art and completed her program in 1941. With a slight smile, she said with a firm nod, “That’s what I wanted to do.”

Engaged while still in art school, Brodie recalled, “My fiancé wanted to get married before I graduated. But I wouldn’t. I insisted I wanted to graduate first.” Of her dream to build a life as an artist, “I was a sculpture major with a minor in watercolor. Obviously, I discovered nobody wanted anybody with that background,” she said.

The couple married in September 1941. Just three months later, the United States entered World War II, and in 1942 their daughter, Chris, was born. Regarding her husband, “He never wanted me to work. But he volunteered [in the war], and he was killed overseas in 1944. Here I was with a 2-year-old, and I lived close to my parents. One of my friends was working at Ohio Rubber, and she said, ‘Why don’t you come?’”

ENGINEER THROUGH APPRENTICESHIP

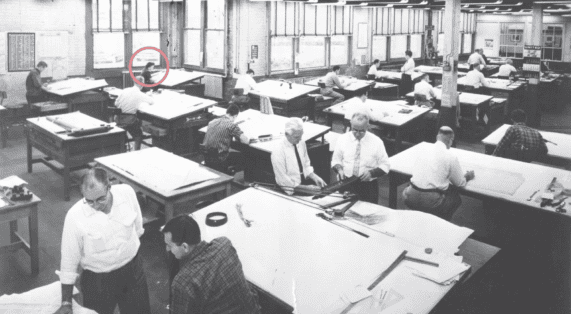

While men were overseas fighting the war, women took their places in factories and in other traditionally male occupations. Brodie joined the ranks of these “Rosie the Riveters,” but after a few weeks on the shop floor, the foreman told her she was wanted in the front office. There, the general manager asked why she wasn’t using her talents and directed her to interview with the engineers in charge of plant engineering and design. “That’s how I got my start,” she said. “I designed molds for them, for years, and then in 1948 I married [again], and still worked.”

Initially, the chief design engineer was skeptical, and assigned her to the blueprint room until she could prove she knew how to use the drawing machine. Figuring that it couldn’t be that much different, or more difficult, than the T-square and triangles she had used in art classes, she took it upon herself to master the drawing machine. “I worked in the blueprint room six weeks. He decided I’d better start drawing, and I never looked back,” Brodie said.

Unlike many of the women who took on traditionally male work during the war and were “pink slipped” when the men came back, Brodie kept her job. And she continued working after marriage — also unusual for the time. In the early 1950s, she had her second daughter, Pam. “At that time, they would only give me three months maternity leave, so I quit.”

Less than three years later, however, she returned. “I went to my boss, former boss, and he said, ‘Are you ready to come back to work?’ And I said, ‘Yes.’ I continued until I retired.” With her husband developing his own business and money being a bit tight at the time, her mother-in-law had suggested she reclaim her old job. Both her mother-in-law and Brodie’s own mother lived nearby and were willing to help with child care and other details of daily life, and so Brodie resumed her work designing molds and, from time to time, parts for the auto industry.

Less than three years later, however, she returned. “I went to my boss, former boss, and he said, ‘Are you ready to come back to work?’ And I said, ‘Yes.’ I continued until I retired.” With her husband developing his own business and money being a bit tight at the time, her mother-in-law had suggested she reclaim her old job. Both her mother-in-law and Brodie’s own mother lived nearby and were willing to help with child care and other details of daily life, and so Brodie resumed her work designing molds and, from time to time, parts for the auto industry.

The Society of Women Engineers was in its early years then, and growing. A chance conversation with a male electrical engineer who told her, “You ought to contact the organization for women engineers,” led her to SWE. In 1963, she applied for senior-level membership. By this time, she had been with Ohio Rubber for 15 years.

In those days, SWE membership applications were carefully scrutinized and required recommendations from employers and colleagues. The chief tool and product engineer wrote: “It is the writer’s understanding that Mrs. Brodie has applied for the senior membership and I believe [she] qualifies … She has been doing design and follow-up work on tooling for rubber parts for the length of her career in this company. Her work has been very thorough and of very good judgment and certainly entitles her to the classification of engineer. While she has not had engineering schooling, firsthand experience has given her the same achievement.”

It’s worth noting that the shift from apprenticeship training to college education for engineers began taking place in the late 19th century, which meant that in the United States, one could become an engineer via on-the-job training well into the 20th century. Historians Margaret Rossiter, Ph.D., and Amy Bix, Ph.D., have discussed how this played out for women who did engineering work, either receiving additional training and the appropriate designation — as happened in Brodie’s case — or not. Echoing the strong recommendation of the chief engineer, her immediate supervisor wrote: “Mrs. Brodie has at her command an excellent knowledge of rubber processing, machine shop practice, and drafting. She is presently employed as a tool engineer and is a leader in the mold engineering department of the Ohio Rubber Co. In this capacity she serves as a designer, checker, trouble-shooter, teacher, and supervisor. Her analytical ability is outstanding. She would be a most welcome addition to any tool engineering department in the rubber industry.”

Several months after her initial application, Brodie received a welcome letter from SWE’s admissions committee, notifying her that she was now a member (not a senior member, however; that would take a few more years). With no local section, she was a member-at-large, and was encouraged to participate in events on the national level. At the close of the letter, admissions chair Betty Yost, P.E., wrote, “We hope you will take an active part in the Society and that you will enjoy your association with other women in engineering.”

MAKING STRIDES

Joining SWE provided Brodie with personal and professional opportunities. As the lone woman engineer in her entire company, meeting with women engineers at the SWE conventions, as they were called at the time, was special. “Once the company learned they could, they paid for my trips to the conventions,” she said, noting how fortunate she was to have both the time off from work and the company pay her way.

From the early 1960s through the ’70s, Brodie worked her way up, becoming senior design engineer in 1970. She continued participating in SWE activities, and over time, she and other women engineers in northeast Ohio built the momentum to establish the Northeast Ohio Section in 1978. In retrospect, developments in both — the workplace and in SWE — appear to have gone hand-in-hand, each enriching the other.

One SWE convention in particular proved to be pivotal. “It was in the East, New Jersey, I think. HP had a computer there — that was when I first met a computer. I came back, and I told my boss about it.” By this point, Brodie was heading the drafting department, among other responsibilities. She enrolled in one of the early computer training courses she could find, and was fascinated. “I was so enchanted with graphics on the computer. That was long before PCs.”

Over time, as a result of attending that SWE convention, “I went from the drafting board to the computer. We wound up with all computers.” As an early adopter of a new technology, Brodie led the way to a transformation at her company. In addition to all the day-to-day operations, from the 1960s through the mid-1980s, she introduced Ohio Rubber to a CAD/CAM system, supervised the startup of the injection molding division, and compiled a tire and mold design manual.

Throughout these demanding but rewarding years, Brodie was keenly aware that the support she received from both her mother and mother-in-law made it possible to avoid some of the work/life integration issues — as described in today’s terms — common to families. “I was fortunate enough to have two grandmothers close and both of my girls were close to their grandmothers, my mother especially,” she said. “Pam’s dad’s mother lived with us for a while, and that helped me a lot. I knew the girls were well taken care of.”

Brodie also became aware that despite her contributions and successes, her salary was not equal to male peers. Inspired by and identifying with the women’s rights movement, she confronted her boss about the pay discrepancy. The outcome was not what she had hoped. His response — “We’ll see what we can do” — translated to a small increase. On the other hand, the controller assured her that her retirement was set up in such a way that it could never be taken from her. And that has remained true.

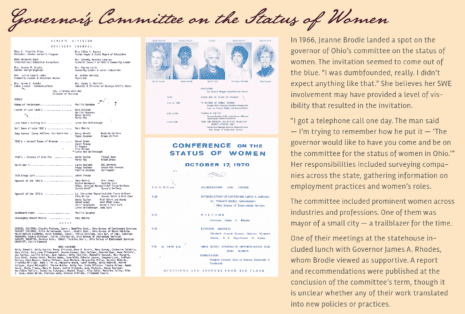

Although disappointed by the continued pay gap, Brodie believed that her efforts — at work, in SWE, and serving on statewide councils and commissions — were contributing to positive change, and a better situation for women overall. She served on the advisory council for the Bureau of Employment Services for three years, concerned with women’s employment issues, as well as on the governor’s commission on the status of women. She continued to participate in outreach activities geared for high school girls, speaking at career days, judging science fairs, and scholarship applications, and fighting for women’s rights in other areas.

Brodie retired for the first time in 1985. When one likes what they’re doing, however, work is much more than a salary. It wasn’t long before she accepted an offer from a former boss who had started his own company. For another 30-plus years, from 1985 until 2016, Brodie worked part time for Ohio Elastomers as a site manager, writing CAD programs and training employees. “I enjoyed it, and I found it interesting,” she said. Describing the invitation from her former boss, “He asked me to come help him, and I could work anything I wanted.” She also was a freelance designer for local companies.

Living in the same senior independent living complex where she currently resides, fellow residents and staff remarked that she was one of the few residents who still drove, let alone drove themselves to work every day. She retired fully at age 97.

TRULY SEEING

“I was very active in art. I was also a member of the art society at the museum of natural history. I used to go there all the time,” Brodie said. Together with a good friend from art school, in her spare time she painted outdoors, weather permitting. Later in life, another good friend and co-founder with Brodie of the SWE Northeast Ohio Section, Peggy Evanich, accompanied her on trips to Maine. There, Brodie spent much of her time painting.

“I used to exhibit [in the Cleveland Museum of Art’s May Show]; I managed to get in most of the time,” she recalled. The show, an annual juried event that took place in the spring, attracted artists across the region. After 75 years, the event was discontinued in 1993, though there have been calls to revive the tradition.

Learning to see has been the dominant theme in Brodie’s life. From reading blueprints as a child to art classes in high school; from formal art training and making plaster molds in sculpture class; to designing industrial molds,

Brodie’s vision and perception have taken her places she may not otherwise have imagined.

More SWE Magazine articles:

- Celebrating the Sun Queen

- Women Engineering Leaders in Academe 2019

- Constructive Voices in Turbulent Times

- Career Pathways: From Unnerving to Victorious

- Spooky Stories in Engineering

- Women Making News: Fall 2019

- Women Lead Three of Four NASA Science Divisions

- SWE Magazine Honored for Publishing Excellence