We celebrate Women’s History Month to both honor the work of past generations and to inspire the future. During this time, you’ll often see profiles of “Great Lives” — women recognized for their extraordinary contributions to society. As inspiring as these stories may be, sometimes it can be difficult to envision oneself as having the same impact as, say, computing pioneer Grace Murray Hopper.

Ordinary people working together can have an extraordinary impact, though. The founding and early members of the Society of Women Engineers included such well-recognized and respected figures as Lillian Moller Gilbreth, Elsie Eaves, Beatrice Hicks, Virginia Tucker — and yes, Grace Murray Hopper. But the Society’s growth and success in its early decades was the product of hundreds of volunteers working together to open the door for women in engineering. Their efforts decades ago paved the way for the vibrant, impactful, international, nearly 50,000-member organization that SWE is today.

Lt. Col. Arminta Harness (USAF, Ret.) celebrated these founding and early members collectively in the following article, published in the March/April 1993 issue of U.S. Woman Engineer (the predecessor to SWE Magazine). As a fellow and a past president (1976-1978) of SWE, Harness was active nationally and in the Los Angeles Section. SWE recognized her service to the Society in 2000, when it bestowed on her the Distinguished Service Award.

— Troy Eller English, SWE Archivist

At the beginning of 1950, the great war effort of the ‘40s had been shut down, industry had cut back across the board and employment for most engineering disciplines was at a minimum. But all that changed in June 1950 with the start of the Korean police action (it was never declared a “war”). Once more, defense industries had to gear up from scratch. Engineers, including women, were needed again.

Unlike the effect of World War II, the short, three-year limited-area Korean “war” did not result in increased numbers of engineering students — and women engineering students in particular. Indeed, for the next two decades, the ratio of graduating women engineers to graduating men engineers remained at the one half of one percent or less range, which makes the continuation and progress of SWE during that period even more remarkable.

Even during the Korean conflict, “career” women were rare. Society’s goals for women were still limited to home and family, teaching and nursing. Any single woman who was working was assumed to be looking for a husband, and a married woman who was working was considered a real oddity — even more so if she was an engineer. Most of the women who joined SWE during the ‘50s and early ‘60s had graduated in the late ‘40s and ‘50s. Little by little, primarily by word of mouth, working women engineers heard of and joined SWE.

By 1954, the original four sections had been joined by 14 others, and the organization was truly national in geographical coverage — with a lot of big gaps like Los Angeles to Denver and Denver to Seattle. Membership, however, only numbered 444. Ten years later, the number of sections had dropped to 15, but total membership had almost doubled. By 1964, there were 16 student sections — exceeding the number of professional sections for the first time. (It should also be noted that Drexel University, one of the schools with a student group called Society of Women Engineers as early as 1948, was chartered as SWE’s first student section in 1954.)

Life as a SWE member during the ‘50s and early ‘60s was as different from that of today’s members as night is to day. She was, of course, a woman (male members were not admitted until 1976), probably unmarried, usually the only woman engineer in her company or government agency, and received absolutely no support from her employer for her SWE activities (although some unsuspecting companies supplied a little typing, reproduction and postage help).

Support and encouragement was also lacking from the engineering society of her discipline. She paid her own way if she attended the annual SWE convention, usually having to take vacation time to attend. If she was a section or society officer, she paid all of her own expenses. This, plus the need for money to run the Society and support career guidance activities, led to many unique and unorthodox money-raising schemes, in addition to the more traditional bake and craft sales.

It was a period of hats and gloves, teas for college students, lots of “first-and-onlys,” and holding the same SWE job over and over again. The limited membership within a section meant that each active member rotated through all the committee and officer chairs and frequently started back over again.

This led to two unique problems when new graduate members started pouring in during the late ‘70s: The “old timers” were so happy to have replacements that they just dumped everything on the “new kids” and disappeared, or they were so used to holding the reins that they wouldn’t let go!

It was in this “home and family” environment that a group of pioneering SWE presidents, officers and members:

- Established the Society of Women Engineers as a nationally recognized organization. (1950-1953)

- Held the first of what would become an annual SWE Convention. (1951)

- Incorporated the Society as a nonprofit, educational service organization. (1952)

- Established the SWE Achievement Award to gain national recognition for the achievements of women engineers. (1952)

- Assisted the Women’s Bureau of the U.S. Department of Labor in the preparation of the first U.S. engineering career guidance publication for women. (1954)

- Established a Board of Trustees to administer funds being raised to support a Society scholarship program and the furnishing and operation of a Society headquarters. (1956)

- Established a SWE headquarters in the newly completed United Engineering Center at the special invitation of the United Engineering Trustees. Prior to that time, the Society operated using a commercial office service contract. (1961)

- Hired the first executive secretary, Winifred Demarest Gifford (later to become Mrs. Herbert A. White), who worked with no paid assistance in the one room office plus a storage vault. (1961)

- Established a new grade of membership, SWE Corporate Member, and recruited Bell Laboratories and General Electric as the first corporations to hold that grade at a cost of $250 annually for each. (1961)

- Sponsored the first International Conference of Women Engineers and Scientists, held in New York City in conjunction with the 14th annual SWE Convention. Over 500 women from 35 countries and all 50 states attended. (1964)

In addition, during this time period, sections and members-at-large worked hard and succeeded in:

- Gaining significant newspaper, radio and TV publicity for both SWE and individual women engineers.

- Getting both public and private schools to include women engineers in their career day programs.

- Allowing SWE to present awards and to have SWE members serve as judges at local and national science fairs.

- Encouraging women engineering students to form SWE student sections.

- Holding career guidance conferences for high school girls to introduce them to engineering as a possible career.

- Ensuring that state-supervised career aptitude tests from high school students included engineering as a possible career for women. This was one of SWE-LA’s greatest achievements in the mid-1950s.

As any currently active SWE member will recognize, much of today’s career guidance activity is a continuation of that started during the ‘50s and ‘60s. One big difference is that work with high school students is now being done more and more by student sections, while professional sections concentrate on guidance and career development for both college students and professional members.

The main difference, however, is that the social environment in which such work is carried out is far less hostile, and the moral and financial support received from both employers and the public are far greater than anyone dreamed of during those beginning years — due in large part to the efforts of that small band of SWE pioneers. We owe them all a big debt of gratitude!

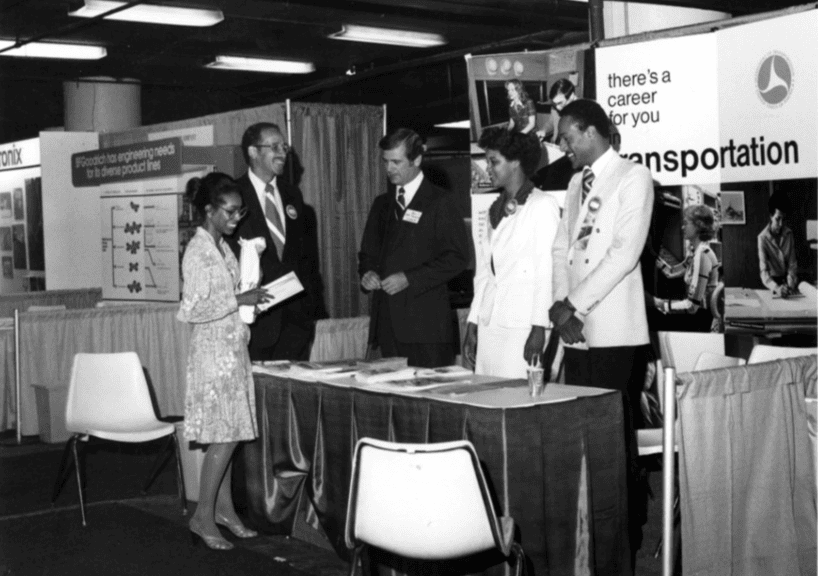

SWE Career Fair: Then and Now

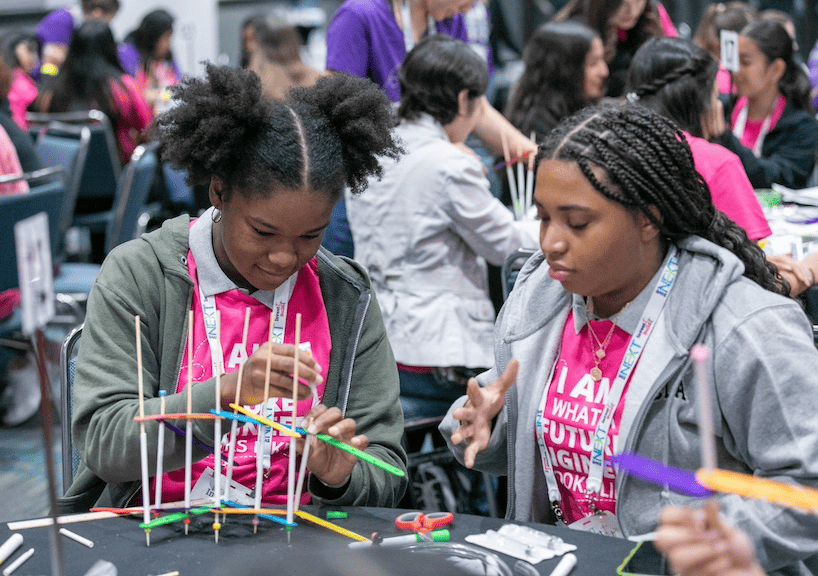

SWE Outreach: Then and Now

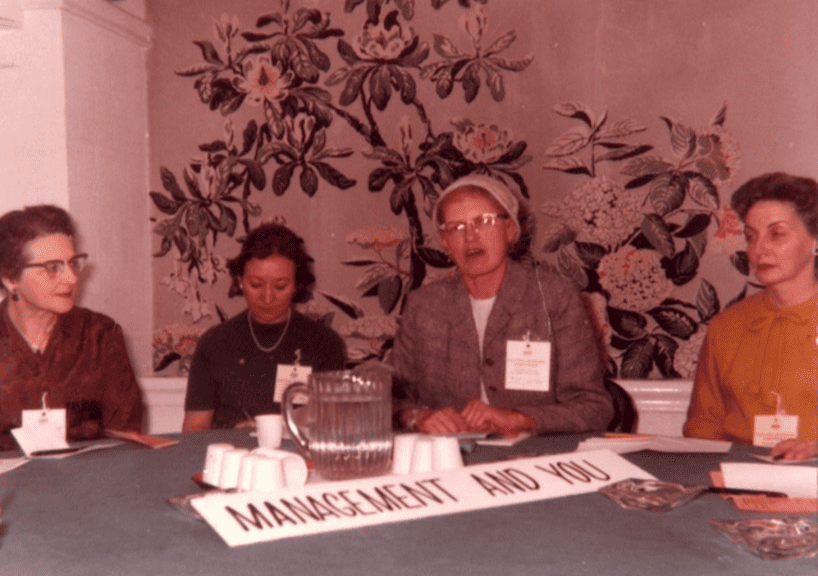

SWE Professional Development: Then and Now

Author

-

SWE Blog provides up-to-date information and news about the Society and how our members are making a difference every day. You’ll find stories about SWE members, engineering, technology, and other STEM-related topics.